Does “risky play” mean the same when you’re under threat of danger?

Play is a typical part of a child’s development, but the term “risky play” takes on a new meaning for those who live in refugee camps, as documented through a research collaboration between the BCIRPU, the American University of Beirut, and the Middle-Eastern and North African Program for Advanced Injury Research (MENA PAIR) in Lebanon.

In North America, risky play commonly refers to a type of active, free play that sparks curiosity and includes thrill-seeking. The benefits of risky play are well-studied, including encouraging physical activity, and helping children improve their sense of self and understanding of the world.

But risky play means something different for children whose safety needs are not addressed, such as those whose families have been displaced in countries affected by war or are under ongoing threat of violence. Dr. Michelle Bauer, BCIRPU Research Associate, and Dr. Samar Al-Hajj, Assistant Research Professor at the American University of Beirut and Director of MENA PAIR, wanted to explore this concept.

“We wanted to know: What does it mean to have opportunities for thrill and excitement and community when anything around you could hurt you—and sometimes intentionally?” said Dr. Bauer.

Dr. Bauer travelled to Lebanon in September and October of 2023, and the two researchers used a partner-oriented approach, building trust among the families living in Syrian refugee camps. They conducted semi-structured interviews and visited families with a team from the American University of Beirut and Yale University to discover what children and their caregivers find most relevant and concerning to them when it comes to injury and play. Findings of this study were published open access in January 2025 in the journal Sociology of Health and Illness.

During the study, researchers found that there was a need to recalibrate their language surrounding play. Children reported limited opportunities to play safely. When asked, “Is there anything you consider risky?” children and their caregivers discussed things about their surroundings that were actually dangerous. This caused Dr. Bauer to reflect on the North American view of risky play that she was bringing to the study.

“How do you convey risk to a community that has been displaced, who have been living without their basic necessities?” Dr. Bauer said. “The families we talked to said that within the camps there was little room for safe play because of cooking equipment, and lack of play structures. They also said that there was a fear of assault and discrimination from others, as well as danger from animals outside of the camps. The concept of ‘risk’ didn’t resonate with them.”

"The families we talked to said that within the camps there was little room for safe play....The concept of [risky play] didn't resonate with them." —Dr. Michelle Bauer

In addition, refugee families faced inequities and had issues accessing health care reliably, increasing the likelihood of them needing to live with the consequences of untreated injuries.

This project is part of an ongoing collaboration that BCIRPU researchers have with the American University of Beirut since Dr. Al-Hajj was first mentored within the BCIRPU while completing her PhD. She received support from the National Institutes of Health to establish MENA PAIR, a research centre similar to the BCIRPU, in Lebanon.

Other work explores injury inequities

Drs. Bauer and Al-Hajj believe there is a need for a movement to retheorize risky play to include non-Westernized perspectives and experiences, and to amplify the voices of children most susceptible to injury.

“As a society, there is a need to focus our attention on the inclusion of different perspectives and experiences, both abroad and right here in Canada,” said Dr. Bauer.

Drs. Bauer and Al-Hajj, along with a passionate research team in Lebanon, are currently working on a study following the internal displacement of Lebanese refugees due to Israeli armed conflict. This new study builds upon previous work to focus on exploring memories of play pre-displacement, and the influence that displacement and other compounding social and environmental factors have on play, identity, and belonging. This includes gaining an understanding of how those working with displaced children can best support play in temporary settlement communities.

Dr. Bauer said that there needs to be a focus on improvements and accessibility for children who face inequities and who are at greater risk for being seriously injured.

“When it comes to injury prevention, children will show you what you have missed,” Dr. Bauer said.

Dr. Bauer would like to thank Dr. Al-Hajj and her team at the American University of Beirut for their invitation to collaborate on this work.

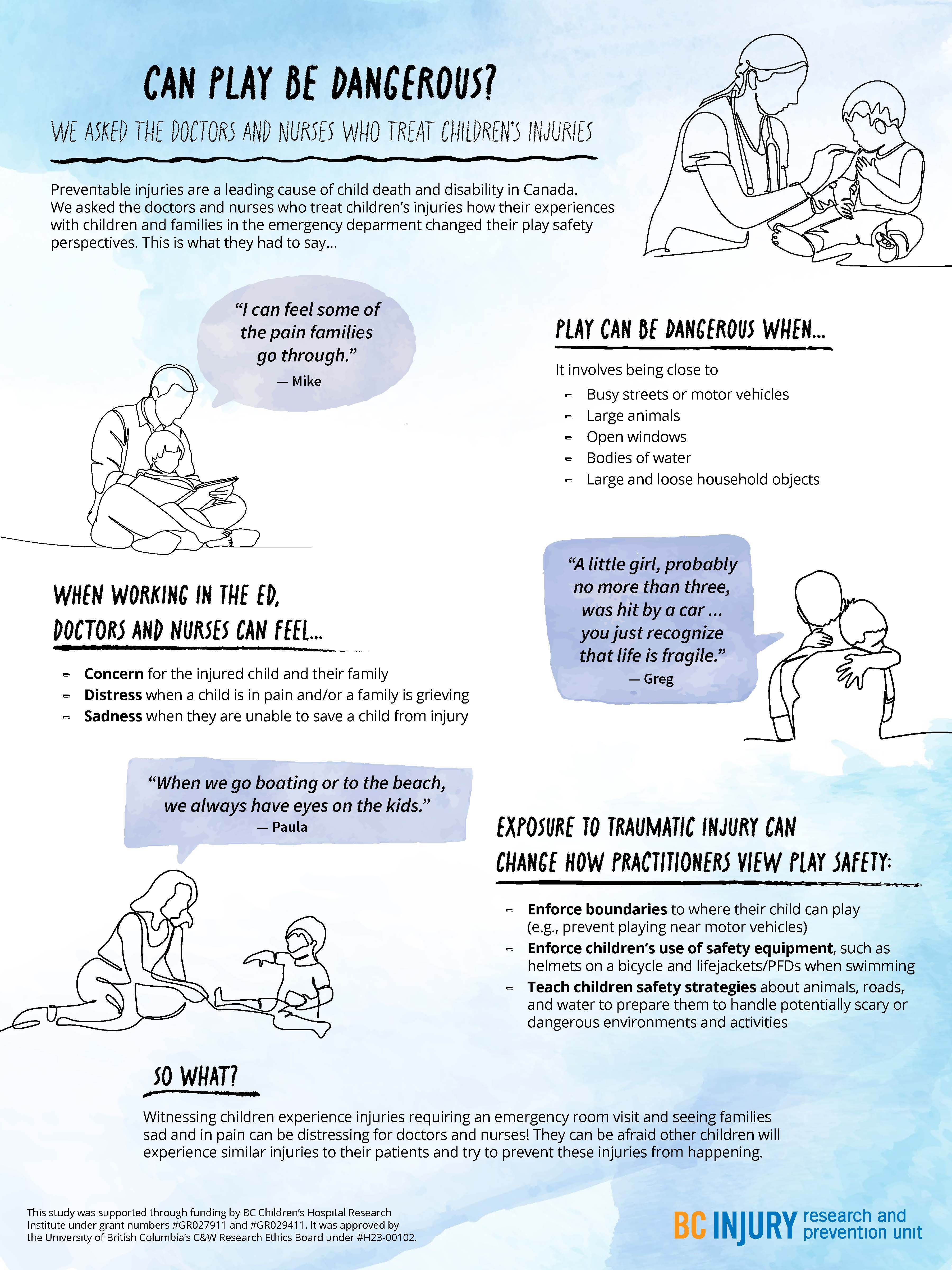

- distress when a child was in pain and when a family was grieving; and

- sadness in the event they were not able to save a child in their care.

- concern for the injured child and the child’s family;

Particularly traumatic events, such as those involving vivid sights and sounds (e.g., families holding each other and having extreme reactions), stuck with the practitioners, having long-lasting impressions on them and causing them to re-live these events in the years following their exposure.

Even after their shift was over, practitioners said that they changed how they approached parenting and how they perceived safety during play as a result of witnessing these traumatic events. They reported having more knowledge of the causes and consequences of severe injuries, such as those that require hospitalization or emergency care. For example, practitioners were more likely to enforce boundaries around where their children could play, such as by forbidding their child to play near busy streets. They also were more likely to tell their child about safe play environments and equipment, and put this equipment on their child before play, such as explaining the benefits of using helmets while riding bikes.

Practitioners were more likely to enforce boundaries around where their children could play, and use safety equipment, such as bike helmets.

Practitioners also described being concerned about their children’s play near open windows, around large bodies of water unsupervised, and in environments where firearms were present. They also expressed worry about their children’s play on trampolines and on motorized vehicles, such as ATVs. Findings related to trampoline play safety concerns were published in the journal Injury Prevention.

Observing family grief due to child injury or death affected the mental well-being of health care practitioners, drawing attention to the need for mental health supports for those involved in caring for severely injured and dying patients.

"Raise more resilient children through play...watch and see how your child handles challenging tasks without intervening right away." —Dr. Michelle Bauer

Building resilience through play

How can parents help their children build resilience? By letting them play!

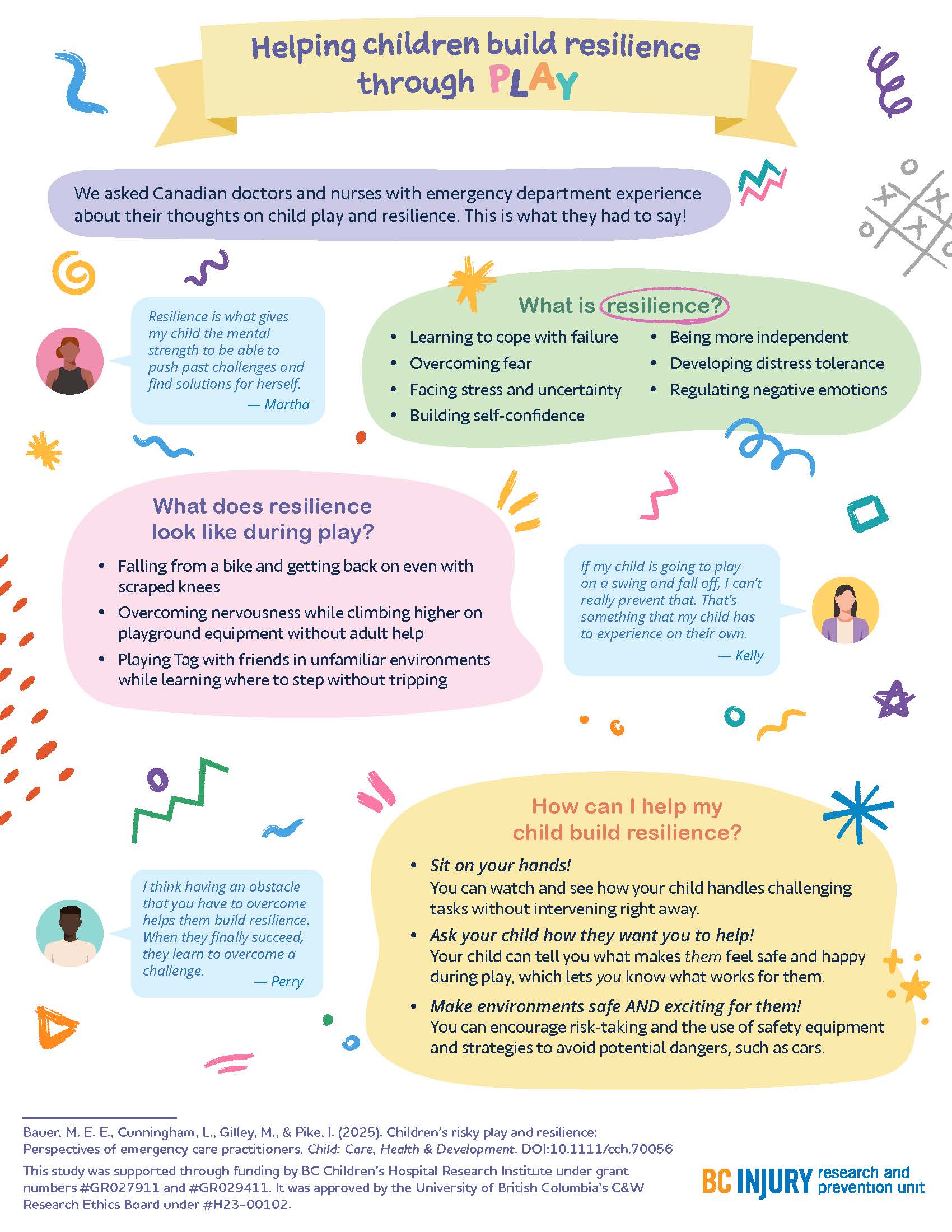

The experiences that practitioners witnessed encouraged them to support their children in building resilience through play; specifically, by supporting children in learning to cope with failure, overcome fear, build self-confidence, develop distress tolerance, and regulate negative emotions. Findings related to building resilience through play were published in the journal Child: Care, Health, and Development.

Parents fostered resilience in their kids by:

- helping their kids get back on bikes after they fell off and wanted to try again;

- sitting on their hands so they did not instinctively reach for their children when their children fell down; and

- encouraging participation in challenging and thrilling activities in forests and water while safety equipment was used.

"There are a few ways that parents can raise more resilient children through play that are supported by literature and our study findings," said Dr. Bauer. "One: watch and see how your child handles challenging tasks without intervening right away."

"Two: Ask your child how they want you to help—let them tell you what makes them feel safe and happy during play. Let them lead. And three: make play both safe and exciting by encouraging risk-taking, teaching them how to avoid hazards, and using safety equipment.”

This research was supported through Drs. Bauer’s and Gilley’s receipt of a clinical and translational research seed grant from the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute (BCCHR), Dr. Bauer’s BCCHR postdoctoral fellowship award, and additional training provided to Dr. Bauer through her participation in the Programs and Institutions Looking to Launch Academic Researchers (PILLAR) program through ENRICH, a national organization training perinatal and child health researchers.

Learn more about the study through two infographic posters:

Graphics and posters by Milica Radosavljevic